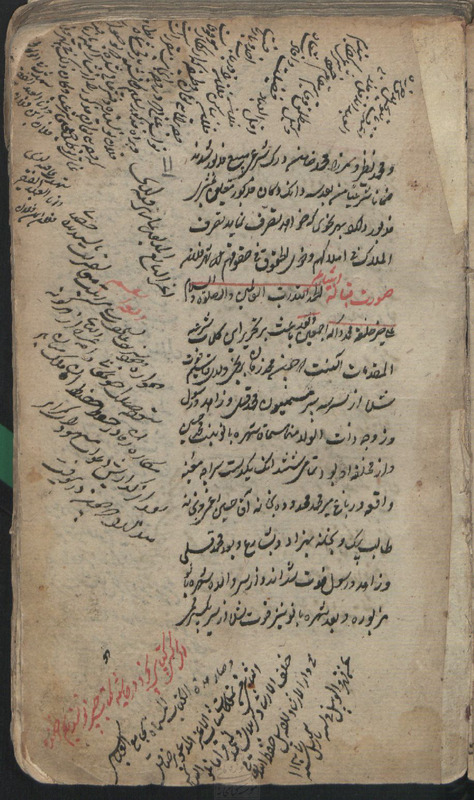

Folio 6 recto

ومحمد نظر و میرزا محمد ضامن درک شرعی مبیع مذبور شدند ضمانا شرعیا من بعد سه دانگ دکان مذبور متعلق به مشتری میرزای مذبور داده بهر نحوی که خواهد تصرف نماید تصرف الملاک فی املاکهم و ذوی الحقوق فی حقوقهم فی شهر فلان.

صورت قباله اشیاء: الحمدلله رب العالمین و الصلوة والسلام علی خیر خلقه محمد و اله اجمعین و بعد باعث بر تحریر این کلمات شرعیه المقدمات آنست که چون محمد زمان برنجی قاسم ولد مش قاسم؟ فوت شده از هر سه پسر مسمیون محمد قلی و زاهد و رسول و زوجه ذات الولد منها مسماة شهره بانو بنت محمد حسین و از مخلقه او بود تمامی شش دانگ یکدست سراچه معینه واقعه در باغ میرمحمد محدوده بخانه آقا حسین قمی و بخانه طالب بیگ و بخانه بهزاد و بشارع و بعد محمد قلی و زاهد و رسول فوت شده اند و از سر والده شهره بانو مزبوره بعد شهره بانو نیز فوت شده از سر یک پسر قمی

Marginalia:

حاشیه: اعترف بالتوکیل لدی حرره العبد الاقل فلانی

وکیل مطلق و قایم مقام خود شرعی گردانیدم اقل العباد فضیلت و افادت شعار فلان بن فلان ساکن فلان را در باب اخذ و بازیافت وجه برات سه تومان وظیفه که از سرکار موقوفات نواب عالی که در وجه اینجانب مقررات است و برات مذکور سلیم براة مذکور تسلیم؟ ابن فلان نویسنده دفتر عالی شده که به وصول که وجه سی تومان مذکور را از مشارالیه بازیافت؟ فلان نویسنده دفتر عالی شده که به وصول؟ که وجه سه تومان مذکور را از مشارالیه بازیافت نمایی؟ تو...صحیح شرعی و کان ذالک فی شهر…

نماید عنایت؟صحیح شرعی و کان ذلک فی شهر فلان ؟ شهدت فی الوکاله و انا العبد الفقیر فلان ابن فلان

شهدت بمافیه لذی و انا العبد الفقیر فلان بن فلان

اعز البائع المذبور بما یر فیه لدی

همواره وجود شریف عالی حضرت سامی رتبت متعالی منزلت پسندیده خصالی ستوده خصلت ادامه الله عزه ازهرگونه مکاره زمان در حفظ حفیظ امان ملک منان باد بعد از گزارش دعوات مشهود را گرامی میدارد که چون درینوقت

اگر کسی کتابی بخرد در حاشیه کتاب چیز نویسد بهم خوانده

و صارهذة الکتاب المسماة بجامع العباسی الثانی من تملکات شاب الاعز المدعو برضاقلی خلف الارشد کربلایی ولیمحمد قرامانلو الساکن فی دار الارشاد الاردبیل حفظه الله تعالی من قهر و الوبیل فی سنه باریس ئیل سنه۱۱۳۷

Translation

Malik 2551 folio 6 recto

And Muhammad Nazar and Mirza Muhammad guaranteed that the sales contract conforms to the Shari’a, a legal (shar’ī) guarantee, and going forward three-sixth portions (dāng) of the aforementioned storefront (dukkān) will be given as possession to the aforementioned customer, to take hold of in whatever manner he wishes, conforming to [the legal formula] “The rights of owners (mallāk) to their property is amongst their rights,” in the month of so-and-so

Copy of an ownership contract of objects: Praise be to Allah the Lord of the worlds, and greetings and peace be upon the best of his creation, Muhammad and his entire family. The purpose of writing these introductory legal (shar’ī) words is that because Muhammad Zamān Birinjī [rice seller/producer], the son of Qāsim, has passed away from the protection of (az sar-i) his three sons named Muhammad Qulī, Zāhid, and Rasūl, and his wife who bore his sons with the name of Shuhrih Bānū daughter of Muhammad Husayn, and amongst what he left behind (mukhallaf) was the entirety of the six portions (dāng) of a specified residence located in the orchard of Mīr Muhammad, which is bounded by the house of Āqā Husayn Qumī/Raghmī, the house of Tālib Bek, the house of Bihzād, and the street (shāri’). Afterward, [the sons of Birinjī] Muhammad Qulī, Zāhid, and Rasūl died, it is inherited by the aforementioned mother, Shuhrih Bānū, and afterward Shuhrih Bānū also died [it is] inherited by a son of Qumī… [cont. on 6 verso]

Marginalia:

I certify to the deputyship here, [and] it is written by the lowly servant [of God] so-and-so.

I confirmed as my absolute representative and deputy, the lowliest of servants, marked by benefits and favors, so-and-so.

So-and-so son of so-and-so, residing in such-and-such, [is] tasked to obtain and recover the draft (barāt) sum of 30 Tumans salary which is due to the undersigned (īnjānib%